The Early History of Ballooning

History of the NBC

The Nebraska Balloon Club came into existence in January, 1977. The BFA (Balloon Federation of America) received notification of an association of balloonists in Nebraska, and Jerry Mahoney of Omaha was listed as the official contact. Charlie Cook initiated the the NBC Newsletter in January, 1977 and listed eleven pilots in the first roster. The first organizational meeting of the Nebraska Balloon Club was held March 19, 1977. Charlie Cook was elected president; Jerry Mahoney, vice-president; and Bill Wemhoff, Secretary/Treasurer.

Thirty years later, the NBC membership rolls have swelled to around 100 members, including 29 pilots and four student pilots. Of the eleven pilots listed in that first newsletter, Jerry Mahoney, Charlie Cook, and Rich Jaworski are still on the club roster. In fact, Rich Jaworski continues flying under the same name and colors: “Euphoria.”

The Early History of Ballooning

In 1783, over 120 years before the Wright Brothers first flight, man lifted himself from Earth in a balloon. On November 21, 1783, in France, Pilatre de Rozier and Marquis d’Arlandes took flight in a balloon built by the Montgolfier brothers. The envelope was made of paper, with straw burned in the middle of a large circular basket. The balloon was tied to the ground until the fire produced sufficient heat to make the system rise. The ropes were then cut, and the balloon rose until the heat was gone.

Just ten days later, Professor Jacques Charles launched the first gas balloon. His system consisted of a varnished silk envelope filled with hydrogen. Since hydrogen is lighter than air, the balloon rose.

The first manned balloon ascension in the United States took place on June 24, 1784 when 13-year old Edward Warren went aloft in a tethered hot air balloon at Bladensburg, MD The balloon had been built by Peter Carnes, a lawyer and tavern keeper from Bladensburg, based on descriptions of the Montgolfier’s experiments. The first balloon flight in this country occured on January 11, 1793, when Jean-Pierre Blanchard lifted off from the Walnut Street Prison yard in Philadelphia in an ascension witnessed by George Washington. (The prison site had been selected to keep out non-paying spectators.) Blanchard’s flight lasted 45 minutes, crossing the Delaware River and landing near present-day Deptford Township, NJ. (Read more about early balloon flights in the United States.)

An interesting side story is how the tradition of the champagne began. When balloons such as the Montgolfiers’ eventually ran out of heat, they began to fall to the ground. This uncontrolled decent often resulted in the balloonists crashing into farmers’ crops. The farmers, having never seen balloons before, would often attack the balloons (and their passengers!) with pitchforks, thinking that they were demons from the sky. The balloonists began carrying champagne along to appease the landowners and show them that they were good Frenchmen. Today, pilots often thank landowners with a bottle of champagne, saluting those make the flight possible.

The Modern Hot-Air Balloon

Photo courtesy of

BallooningHistory.com

No history of ballooning would be complete without acknowledging the contributions of Paul “Ed” Yost, inventor of the modern hot-air balloon. “Ed Yost is our Wilbur and Orville” one pilot recently observed. Ed’s contributions to all forms of ballooning: scientific, gas, and hot-air, advanced the state of the art, and contributed directly to the development of the sport of ballooning as we know it today. Ed helped found the Balloon Federation of America (BFA) and organized the first US National Ballooning Championship at Indianola, Iowa. To get a sense of how far we’ve come in such a very short time, read the report written by Ed Yost in 1963 at the conclusion of a program that resulted in the invention of the modern hot-air balloon. We Nebraska Balloon Club balloonists feel a special kinship with Ed Yost. He was born in 1919 “next door” in the north-central Iowa town of Bristow, and made the first test flight of his modern, propane-powered hot-air balloon on October 22, 1960 at the former Bruning Army Airfield (by then, named Bruning State Airport) east of Bruning, Nebraska (see photo above).

We mourn Ed’s passing in Taos, New Mexico on May 27, 2007 at the age of 87, and celebrate his many achievements each time we take flight in the balloons he invented, and which held such a special place in his life. Those wishing to learn more about Ed Yost and his amazing career, including Channel Champ, the balloon Ed designed, built, and flew across the English Channel in 1964 with Don Piccard, are invited to visit the National Balloon Museum in Indianola, Iowa.

The Physics of Ballooning

There are today, for practical purposes, two kinds of balloons: hot air balloons and gas balloons. Both rely on simple principles of physics for flight.

For a hot air balloon, as the air inside is heated it expands, making it less dense. Because there are fewer molecules per given volume, it weighs less than the non-heated ambient air. This causes the balloon to rise. The balloon rises as long as a sufficient heat differential is maintained between the air inside the balloon and the air outside the balloon. Heat is constantly being lost from the balloon by radiation, through seams, and small pores in the fabric. Thus balloons must carry fuel on board to heat the air inside. To go up, the balloonist adds heat. To go down, he allows the balloon to cool. A typical modern balloon flight lasts from 1-3 hours.

Gas balloons rely on the lifting power of helium (common in the US), hydrogen (more common in Europe), or even ammonia gas, contained within a sealed envelope. Altitude is maintained by releasing ballast (sand or water) to lighten the aircraft, or by venting gas (to decrease lift). A gas balloon flight can last as long as the ballast holds out, up to several days.

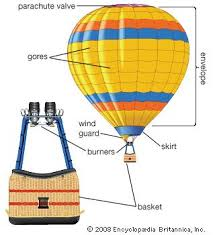

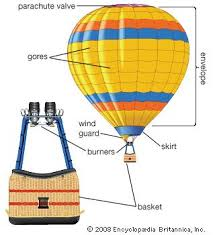

Parts of a Modern Hot Air Balloon

There are three basic parts to a modern-day hot air balloon. First is the basket. Modern day baskets, like those of 200 years ago, are made of wicker or rattan. Uncountable modern-day products have been experimented with, but none offer the combination of strength and flexibility of wicker and rattan. Baskets range in size from those which carry only one person to those which carry over 20 people. the typical hot air balloon basket will carry 2-3 average sized people on an average day. Inside the basket is where the fuel is carried. Today the fuel of choice is propane, the same type that is put into backyard gas grills. (Some pilots use butane or a propane/butane mix.) Most baskets can carry between 20 and 50 gallons of propane, stored in 10-25 gallon stainless steel or aluminum cylinders. Also inside the basket are instruments (typically an altimeter, a variometer, and pyrometer indicating a temperature reading inside the balloon), a “drop-line” (a nylon rope), and a fire extinguisher. The typical balloon basket costs between $5,000 and $12,000 new.

The second part of a hot air balloon system is the burner. It draws fuel from the cylinders in the basket and ignites it, spraying the resultant flame into the balloon. To do this, a pilot light is lit at inflation. The pilot controls the flame with a blast valve. When he opens the blast valve, the liquid fuel under pressure in the cylinders expands down the fuel hoses. The liquid enters the burner, then proceeds through a series of coils located at the base of the flame. Here, the liquid is heated from previous ignitions, and changes into a gas. The gas is then sprayed onto the pilot light, resulting in the magnificent blue flame. Pilots have the option of bypassing the coils and spraying liquid propane onto the burner. This produces a less-powerful, less compact yellow flame that results in less heat, but also in less noise. It is useful when flying over livestock that are easily scared. The system is designed with power in mind: today’s powerful burners are capable of producing 40,000,000 BTU’s per hour.

The third, and surely most visible, part of the modern balloon system is the envelope. This is the actual balloon. Typically made of rip-stop nylon or polyester (some companies, most notably The Balloon Works, are experimenting with non-rip-stop materials). The envelope can be as simple as a one color, standard balloon shape or as complex as a multi-colored Harley Davidson shape. The imagination (and the pocketbook) is about the only limit. The envelope is made of dozens of individual “panels”, sewn together. It is coated on the inside with a “glaze” to help the material retain heat. This coating is gradually worn away by the intense heat (up to 275 degrees Fahrenheit) inside the balloon, resulting in an envelope life of approximately 500 flight hours. Envelopes cannot be easily re-coated to extend their life. There is at least one “vent” in the envelope. With the help of a line extended from the vent to the basket, the pilot can open the vent, either to descend during flight or to deflate the balloon. Prices for a new envelope can range from $14,000 to over $300,000.

The Legal Aspect of Ballooning in the USA

Ballooning in the USA is regulated exactly as is every other form of flight. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulates all ballooning in the USA. Each balloon system is a registered aircraft with the FAA. Every 100 hours or 1 year, whichever comes first, the entire system must be inspected by an FAA-certified inspector to ensure its continued airworthiness. All repairs done on a balloon must be done by FAA-certified repairperson. Each system is assigned a registration number (in the US, this is called the “N-number,” as N will be the first character).

Anyone who operates a balloon must hold a certificate from the FAA. There are three levels of pilot certificates: student, private, and commercial. A student pilot is one who is learning to fly. The holder of a student pilot certificate may only operate the balloon under the direct supervision (in the basket) of a licensed commercial pilot, until they have demonstrated that they can control the aircraft. The student is then “signed off to solo,” meaning that they can fly alone, with no one else in the basket. At no time may a student pilot carry anyone other than their instructor. A private pilot certificate is the next step after student. A private pilot has: 1) completed at least 10 pilot-in-command (PIC) hours; 2) passed an FAA written examination; 3) passed an FAA flight examination; and 4) passed an FAA oral examination. Once certified as a private pilot, a person may take passengers with him, but may not charge them for the ride. The final certificate one can earn is the commercial pilot. A commercial pilot has: 1) completed at least 35 pilot in command hours; 2) passed another FAA written examination; 3) passed another FAA flight examination; and 4) passed another FAA oral examination. Once certified as commercial, a pilot may charge others for rides in their balloon. She or he may also instruct student pilots.

Balloon flight is governed by many of the same laws as fixed wing flight. Altitude and airspace restrictions are enforced, although some are modified for the obvious difference in the aircraft.

Overview of a Typical Balloon Flight

Many hours before the balloon leaves the ground, preparation for the flight has begun. The pilot closely monitors the weather conditions, in particular the wind. Severe weather is obviously not conducive to ballooning, but rain and strong wind are not good either. Ballooning can take place year-round, even in the cold of winter. Wind speed and direction are of particular importance to a pilot. Wind speed under 10 knots are best for ballooning, although competition balloonists will sometimes fly in 20+ knots. Because the balloon travels in the exact direction of the wind, a pilot must select a launch site with the direction and speed in mind, ensuring that they will have adequate site selections for landing. An adequate launch site is anywhere that is large enough to lay the balloon out in, and is without obstacles like power lines and trees. Except in the winter, ballooning safely take place only at sunrise and 2 hours before sunset. This is due to the uneven heating of the earth by the sun, resulting in thermals. The typical summer balloon flight lasts between 1 and 2 hours.

Not many balloon flights can take place without a crew. The crew assists with the inflation and deflation of the balloon and follows the balloon in the chase vehicle. Once a launch site is selected, the pilot and crew sets up the system for inflation. This involves laying the entire aircraft on the ground. Two crew members hold the balloon open near the basket (the mouth), while a large (typically 5-10 horsepower) gasoline or propane powered fan blows cold air into the envelope. This starts the “cold-inflation.” While the balloon is inflating, the pilot inspects the aircraft. This includes ensuring that the previously mentioned vents are properly closed. When the balloon is between 40% and 70% full of cold air, the pilot will begin the “hot inflation.” This involves blasting the flame into the cold air filled envelope. This quickly heats the air inside, causing the balloon to lift. Soon the balloon is standing upright. Passengers are loaded, and the pilot readies for launch. The pilot continues to add heat to the balloon, waiting for the air inside to become hot enough for the balloon to rise. Soon the balloon slowly lifts off the ground, into the sky. The flight has begun.

The pilot has no way of “steering” a balloon. It travels in the same direction as the wind. He or she can, however, find different directional winds at different altitudes. In this way he is offered some form of horizontal control. Ballooning was once described as extremely precise vertical control (within inches, if you’re good), with very little horizontal control. Usually balloonists remain between 500 and 5,000 feet above the ground. Flight above 14,000 feet cannot legally take place without special equipment. The balloon travels at exactly the speed of the wind. During some distance competitions, when competitors are flying above 10,000 feet, the speed can be above 100 miles per hour.

Throughout the flight, the chase crew is following along on the ground. While the balloon flies in a straight line, the chase crew must contend with the constraints offered by roads, rivers, and highways. Although radios are often used, a good chase crew can not only follow the balloon, but predict a landing site and meet the pilot there without even talking to them. Ideally a crew arrives at the landing site before the balloon does in order to secure landing permission from the land owner. Once permission is granted, the balloon will, if the site is in its flight path, approach to land. A landing site typically needs to be larger than a launch site, as the balloon often skids and drags before coming to a halt. A good crew will assist the pilot with his landing, “catching” the baskets and holding it down once it is on the ground. A landing in light (less than 5 miles per hour) winds can result in beautiful, stand up, no drag landings. A landing in heavy (>15 miles per hour) winds can result in powerful, lay-down landings where the basket may drag up to several hundred feet. Pilots try to avoid these situations, as a balloon landing at 10 miles per hour carries with it over 4 tons (8000 pounds) of momentum.

Once the pilot has landed the balloon, it is packed up and placed on the chase vehicle. The average balloon system can be carried entirely on a small pickup. The pilot then thanks the crew and landowner, typically by performing the traditional champagne toast.

Competition Ballooning

Much of the ballooning population of the world chooses to remain recreational, flying simply for fun. This is the purest form of ballooning. Others choose to make their livings flying rides in their balloon (most ride operations charge between $150 and $250 per person for a 1 hour flight). There are a select few balloonists who choose to put their piloting skills up against those of others. These pilots compete in balloon events, also called races or rallies. These events are generally not a competition of speed or distance, but instead a test of accuracy. A goal is chosen before launch (either by the pilot himself or by a head event official, called the balloonmeister), and the pilot is judged on how close to that target he can fly. Targets are extremely specific, often intersections of roads (the exact point at which the two center lines cross). Pilots often must launch several miles from their target, using the variation of wind directions at different altitudes to “steer” their aircraft towards their target. When they are as close to the target as possible, they drop a baggie with a streamer tail at it. How close do the baggies get? Many drops are measured in inches. At an event like the U.S. Nationals (where only the top 100 pilots in the USA are invited), many drops each day are measured with a ruler. Drops of 0’0″ are not uncommon. A pilot’s drop is scored against the best drop of the day, and points from 0-1000 are awarded. Map reading, weather forecasting, and organization are essential skills.

The sport of competition ballooning is extremely organized, and often extremely serious business. Top prize at the U.S. Nationals each year is in excess of $15,000. Most events have special contests where pilots can win new automobiles, balloon systems, and cash, with some advertising prizes as great as $50,000. There is an elaborate national ranking system, and every two years the top pilots in the world gather to compete in the World Championships. The typical balloon event is three days long, although larger events such as the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta, or the National Balloon Classic in Indianola, IA, usually last nine days. Pilots compete once in the morning and once in the evening, with a day usually beginning at 4:00am and ending near midnight. As intense as the competition is, balloon events are also social gatherings. Pilots often travel thousands of miles to compete, so long distance friends are often seen.